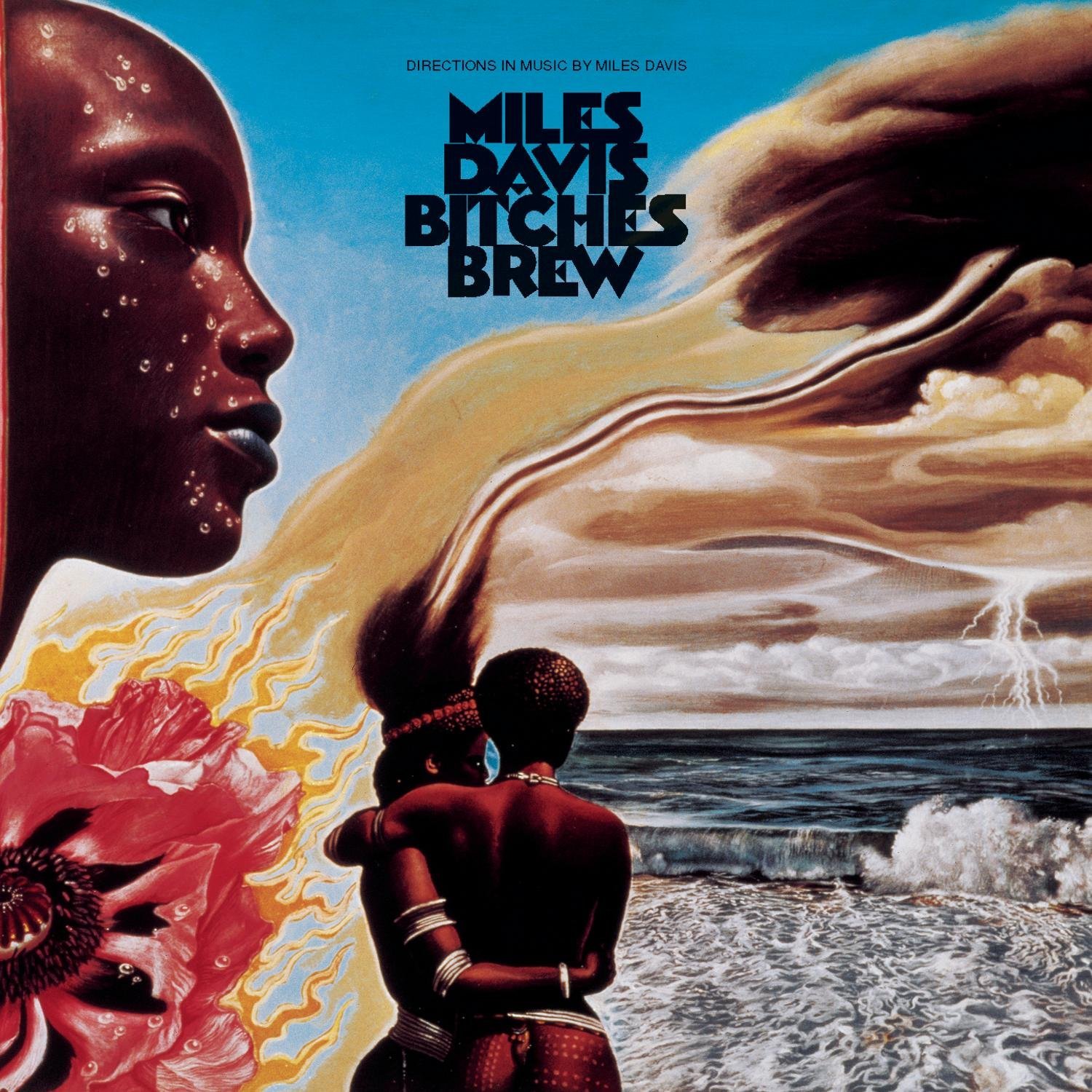

177. Miles Davis – Bitches Brew

This is where I start to struggle. This isn’t the first time I’ve alluded to the fact that I can’t quite get my head around the whole jazz thing, but as those lucky few who’ve followed this blog will know, I’ve had a few pleasurable surprises from the likes of Thelonious Monk and Charles Mingus, and even Miles Davis himself. When things start to approach the jazz-fusion event horizon though, I begin to feel like I’m out of my depth.

This is where I start to struggle. This isn’t the first time I’ve alluded to the fact that I can’t quite get my head around the whole jazz thing, but as those lucky few who’ve followed this blog will know, I’ve had a few pleasurable surprises from the likes of Thelonious Monk and Charles Mingus, and even Miles Davis himself. When things start to approach the jazz-fusion event horizon though, I begin to feel like I’m out of my depth.

“Bitches Brew” though, as any proper jazz devotee will tell you while stroking their goatees, is THE BOLLOCKS – an epic, groundbreaking milestone in the genre, one that changed everything.

And we have Miles’s midlife crisis to thank. Hitting 40 and breathing in the heady vapours of flower power, he was overly conscious that his crown of head dude of contemporary jazz was slipping. He started recording this album on August 18 1969, just hours after Hendrix tore music a new orifice on stage at Woodstock. Hendrix was on his mind for this album, and the influence that “Electric Ladyland” had on its production is often noted – he even takes up arms against Jimi with “Miles Runs the Voodoo Down”.

Miles and Jimi had met by then, and even talked of one day working together, an eye-watering concept of a collaboration. It was Davis’s second wife, Betty Mabry, who introduced them, and, at just 22 years old and surrounded by rock and funk, her influence on this album is now well-acknowledged.

What effect all those influences has is hard to pin down. The opening “Pharoah’s Dance” starts off with a conventional mix of clarinet and electric piano, but it’s not long before the knots start to loosen and things get more convoluted (not before a jarring edit crossover at 1:38 though). Soon the complexity of what’s going on starts to show itself, and the realisation that you’ve got three pianos, two drummers and two bass guitarists all throwing in starts to dawn. As the track goes on, those elements start to sound more disparate and the whole thing reeks of anarchy, but interestingly it all comes together in the last couple of minutes. It’s a noisy, messy and scattershot ride, but there’s a lot to absorb.

Title track “Bitches Brew” brings down the tempo but raises the crazy, stepping away from the trademark rhythmic feel of the rest of the album. It’s a 27-minute-long epic that’s a lot to digest, but it’s certainly interesting – each musician gets a chance to show off, and by the 22-minute mark you’re quite pleasantly absorbed by the whole thing. I was even reminded (and I’m not sure why) of “Sign o’ The Times”-era Prince. Maybe it’s their shared love for a good groovy jam session.

“Spanish Key” sounds more like the jazz-rock-funk-fusion that the album is famed for, complete with some dirty bass chords and a substantial groove, and actually feels a lot more accessible, though just as multi-textured as what went before. There’s still a lot to take in though, and at the 10-minute mark you begin to realise that the traditional idea of a jazz album working as a soothing background to your introspection doesn’t quite gel anymore. There’s so much going on, so many divergent elements coming through the speakers, that it demands concentration.

While there’s not much to really note about the surprisingly short “John McLaughlin” (except for the fact Miles doesn’t even appear on it), things get proper exciting on “Miles Runs the Voodoo Down”. While it sounds absolutely nothing like Hendrix, it’s pretty clear that the long frenetic jams of “Electric Ladyland” were being emulated here, and it’s rich both in pleasing basslines and some utterly insane electric piano work. There’s even a brief moment at 1:30 where I thought I could hear the bass from Jefferson Airplane’s “White Rabbit”, although maybe not.

It’s probably the highlight of the album, it’s certainly the point where things get exciting. It’s also the point where Davis’s own trumpet gets the best workout, and there’s something soothing about that.

The album closes with Wayne Shorter’s “Sanctuary”, a track that had been recorded previously and far more conventionally. It begins so, so gently and sounds more conventional than the madness that preceded it, and it ebbs and flows pleasantly (with a nice little breather around the 5-minute mark).

“Bitches Brew” is certainly epic in scope, and it’s a testament to Davis’s skill that an album with so much going on doesn’t sound like a complete clusterfuck. In fact, it’s so frenetic and multi-layered that a brief few listens doesn’t really do it justice. Suffice it to say that while this level of experimentalism might not be to everyone’s tastes, no one could describe this album as being dull.